Nial Gooding

Monday, May 19th 2014

Preamble

Torture data long enough and it’ll tell you anything. This is especially true in China because not only do we have a lot of it these days but also it’s supplemented by work from a small army of subscription-seeking axe-grinders. In this note though, as far as it’s possible, I want to avoid data ah-hah-ing and present a simple narrative of events that led to the rapid credit growth that’s taken place in China in recent years. Then, I’ll discuss the response and its effects and finally spend a little time on what we might reasonably expect next.

My point throughout will be that nothing has happened in recent years in China that a first year economics student would have trouble grasping. The credit growth, its effects and the policy response have all been text-book in their motivation and execution. Far from presenting a picture of a clueless and fumbling administration the history of this cycle will in time be more fairly assessed as a period when policy makers brought their A-game and wrangled a nuts–difficult situation to a successful conclusion.

Let’s begin at the beginning.

2008 – The Stimulus That Wasn’t

On November 9th 2008 the Chinese government announced an Rmb4trn (U$600bn) ‘stimulus’ package. The number was important as it was almost exactly the same size as a package the US had announced not long before; but China’s economy being that much smaller, proportionally, this represented a much bigger commitment. The shock and awe intended came through and not only was there widespread praise (the

World Bank President Mr. Robert Zoellick, among others, was ‘delighted’) but also stock markets globally rose in direct response. Just one problem, nobody said where the money was supposed to come from?

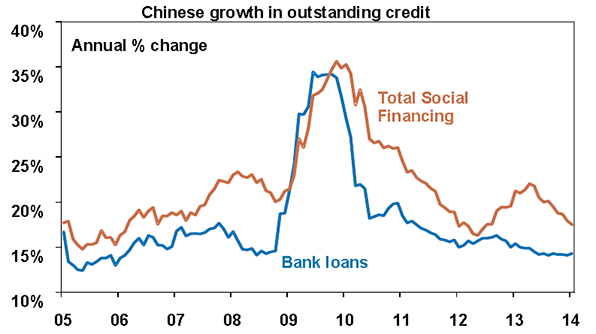

As it turned out what the Central Government was really saying to their regional managers was ‘You know that plan you guys had to build that new bridge/highway/airport? Sure, we’ve been slow to get back to you all with official consent but do it, do it now!’ There was no central government largesse, there was no massive money printing (there was some) and there were no fresh taxes proposed to pay for all this. So where was the money to come from? What would our first year economics student suggest? Correct, you would now need a lot of credit to begin and then continue executing the plan; and this is where the pig went in, as you can see here.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

The Immediate Consequences

What are we taught to expect as a consequence of a rapid credit expansion? Three things can usually be relied on to pitch up; a stronger economy, a pickup in inflation and probably some form of asset price inflation. As it turned out China got all three.

The growth lift was fine but it was soon clear that inflation and home prices, unless checked, could run away. Inflation is a particularly sensitive issue in China as in the past it’s been the root cause of major social unrest. Property prices, historically, had been less of a worry. The unspoken rule of thumb there being that as long as they kept pace with overall GDP growth that’d be fine. As 2009 progressed though it was clear that home price rises were coming through in multiples of GDP growth; and that couldn’t be tolerated.

The Response

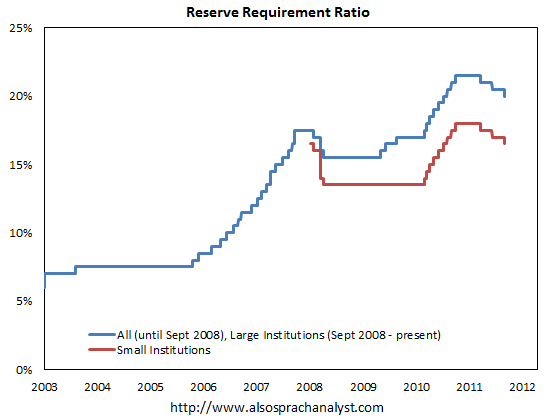

You’re going too fast but you don’t want to stop, so? Simple, brake. In China though, because the financial system was (and still is) at a rudimentary stage of development monetary policy can only be part of a response. However, rates and liquidity were tightened and one of the most public examples at this time was the move in the Reserve Requirement Ratio or RRR.

What the chart below reminds us is that prior to the GFC China had been busy tightening since 2006 in an attempt to check the inflation that was being transmitted by persistently higher commodity prices. [Ironically, it could be argued with 20-20 hindsight, China didn’t need a stimulus at all?]

Source: Bloomberg

The rapid rise in home prices was tackled via an intervention by the State Council in April 2010. They announced a package of measures increasing mortgage down payments, limits to multiple home ownership and making mortgages more costly. Most importantly this process made it crystal clear that the situation was being addressed at the highest level; State Council intervention being the policy equivalent of a nuclear response.

Also at or around this time the term LGFV (Local Government Finance Vehicle) began to appear more frequently. The sharp eyed had noticed these old but mostly dormant vehicles had recently done a bit of a Lazarus, and some. The government noticed too and announced an audit (the first of three that have since taken place) which took place between March and May 2011 involving 3,000 local authorities (intended I suspect more as a shot across the bows of the more profligate rather than as part of a campaign to shut the financing conduit down).

The main point to mind here is that as far back as 2010, four years ago, China’s planners had noticed unwelcome consequences of the 2008 stimulus and were acting to curb the more dangerous excesses.

The Effects

What would our first year economics student predict the outcome of this response to be?

They’d probably tell us that inflation was likely to fall in response to monetary tightening, home price rises would moderate if transactions became harder to perform and bad debts were likely to increase if only because the overall amount of debt had gone up. Finally, the quid pro quo of attempting to simultaneously tame credit, inflation and asset price beasts would likely be a slower economy.

Unsurprisingly then here we are half way through 2014 with all the above.

Inflation is back in its box.

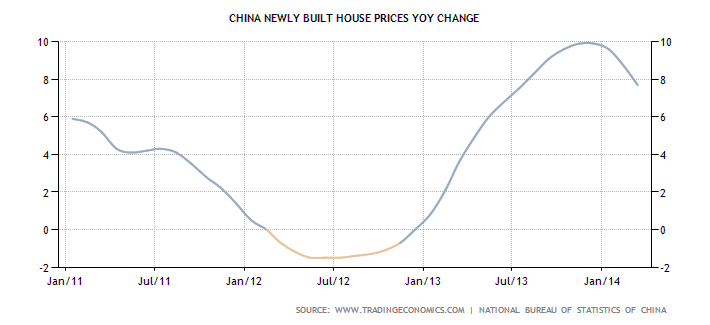

The jury is still out on home prices. After initial success these seemed to get fresh wind last year but the most recent data suggests that they’re again in retreat.

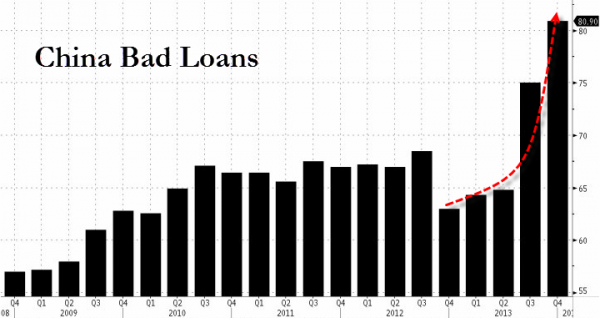

Bad debts have, of course, gone up; the latest reporting being greeted with fresh glee by doomsters.

There a couple of issues with bad debt though. As already noted if loans rise, which in a growing economy they’re bound to, then the absolute level of bad loans must surely follow. Q.E.D. What’s important to keep track of though is what proportion of total loans are going sour?

Data from the big banks show that NPL levels are indeed rising; but only from extremely low to low. The CBRC told us in February that the system wide NPL ratio had risen to 1% (and it’s likely to go higher); but is this really a dagger pointed at the heart of the financial system? I don’t think so. [Even if the true NPL number is several multiples of the official one; which, incidentally, I don’t believe it is. As an aside here I note cynics lay great store by official China data when poor but refute its credibility when it fails to fit their arguments. Me? I don’t fully trust the numbers either but do believe they accurately reflect broad trends]

Finally, receiving perhaps the widest press recently, the economy has slowed; and is likely to slow further.

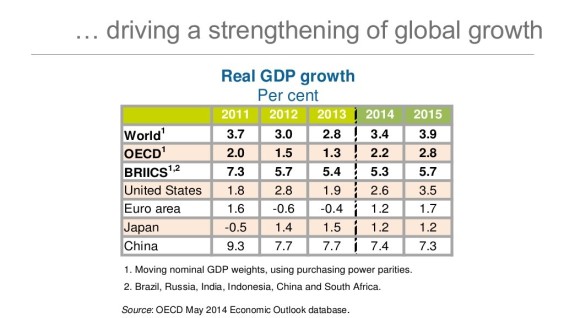

Come on though, give the managers of China Inc. a break. No other major economy is producing growth even half of what China is likely to produce in the next two years. Moreover, unlike recovering victims of GFC excess, China isn’t coming off a low base; it’s managing a controlled descent from an unsustainably high one.

What Next?

We can’t know for sure but if we continue to follow our first year student’s textbook some things seem likely.

It seems likely that policy will evolve to address some of the negative effects of a selectively overly tight monetary policy. The deteriorating receivables situation for example that’s affecting large parts of China’s corporate sector and has been getting steadily worse for the last couple of years can’t be allowed to progress. If companies could get comfort that credit would be more reliably available than it has been in recent years the vicious circle of payment hoarding would be broken. This could be one of the big welcome surprises of this year.

[I thought about tossing in something here about Renminbi weakness and how that amounts to de facto monetary easing but personally I don’t believe the exchange rate is being employed directly as a domestic monetary control tool. More on that perhaps in another note?]

It seems likely also that fiscal policy, particularly with regard to the housing sector, may be relaxed some. We’ve already heard of some municipalities moderating the terms of their specific Home Price Restriction (HPR) policies. Expect more of this as the year progresses. China’s housing market is demand not speculator led and making it hard for people to improve their living standards by dint of their independent effort and resource is bad long term politics. Don’t expect any major nationwide HPR announcements though, just clear smoke signals from the periphery. Which are already rising.

Finally, it also seems likely that the old modus operandi of selectively squirting patronage into areas that need a lift will return; and we’ve also already seen some signs of this. Premier Mr. Li Keqiang in April announced what was called a (read-his-lips) mini-stimulus and my guess is this is how development will progress for the next couple of years. Much, in fact as it always had done, before the 2008 splurge.

In Conclusion

In this note I’ve deliberately over simplified a complex dynamic; but that was my intention in order to separate reality wood from agenda-driven commentators’ trees. I’ve purposely avoided, mostly for the sake of brevity, going into shadow banking and the rise of all off balance sheet lending because I don’t think it’s important to the broader argument. Those developments are interesting (also probably worthy of a separate note in due course?) but only as footnotes to the broader narrative. Which, to remind, is this; China had a credit blow out, noticed, set about grappling with it and now, after several years of sustained effort, has a grip on it.

What matters now is not interminable raking over of this but what’s to come? That, I believe, is more balanced, sustainable and reliable growth than we’ve enjoyed in recent years; and who doesn’t want that?