Another IMF Working Paper. I noted last week, summarizing the one highlighted then, how IMF recommendations on China have a habit of ending up as official domestic policy. So these papers are especially worth paying attention to.

In this one, from January this year, IMF staffers Sally Chen and Joon Shik Kang begin by reminding us that although there’s no consensus on what a wrong or dangerous level of debt might be there are clear and observable negative consequences of what happens when credit cycles end badly.

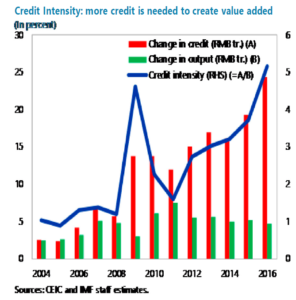

Here’s the kernel of why more debt in China has recently been a bad thing.

The blue line is credit intensity i.e. the amount of debt required to produce a given level of output. As you can see the line not only trends upwards but in recent years the trajectory has become steeper.

The blue line is credit intensity i.e. the amount of debt required to produce a given level of output. As you can see the line not only trends upwards but in recent years the trajectory has become steeper.

Of course, this can’t go on. SOEs account for half of credit advanced and while that’s down from around 60% prior to the GFC they are poor allocators of resource and crowd out more worthy, and productive, recipients.

The paper highlights there’s no historical precedent for a credit expansion of the size and duration that’s taken place in China and, more worryingly, there’s also no precedent for an economy coming off such an expansion well.

So, to the main point of the paper; can China specific factors save China from a credit bust?

The answer is nuanced. No, China if it continues with present trends, cannot be saved from a bust; and, given the scale of the boom, an uncontrolled bust would result in problems of biblical proportion. However, and here’s the good news, China specific factors should make a controlled roll-back of credit easier.

Specifically:

1) China has a strong external position. It runs a persistent current account surplus and has piffling amounts of foreign currency denominated debt.

2) It has a high domestic savings rate. Its banks are funded by depositors with, practically, nowhere else to go.

3) Asset values have been strong lowering for many corporate borrowers debt/asset ratios in recent years.

4) It enjoys what the authors somewhat euphemistically refer to as ‘ample fiscal space’. That is the state continues to be the most important agent in the economy.

5) The capital account is still relatively closed and capital controls, as witnessed by actions in the last 18-months, are effective.

6) The economy will most likely continue to grow strongly and this will result in further financial deepening.

So what’s the cure? SOE reform (the subject of last week’s paper. Coincidence? I think not) must be energetically progressed. Rein in the shadow banking complex (already underway). Apply increasingly commercial standards to lending by the state’s biggest creditors, the banks. Develop a resolution architecture to prevent piecemeal response to problems. Make bankruptcy easy and more acceptable and use macroprudential measures, not monetary policy, to prevent systemic instability.

The authors conclude (P. 16) the situation is grave, and doing nothing will surely end in calamity; but there is hope. Moving away from a growth-at-all-costs mindset (also, already underway), facing some hard truths about which parts of the economy (mostly SOEs) are causing the biggest problems and stopping the growth of systemic unproductive lending are solutions all within policy maker’s grasp.

I believe China will de-fang it’s leverage problem and there are signs, now in plain sight, it’s already moving to resolve some of the more pressing issues. The paper is a valuable reminder though of the consequences of timidity and how we’ve now reached the end of a road down which this can cannot be kicked further.

You can read the paper in full via this link Credit Booms – Is China Different?

Happy Sunday