Summary Conclusion

The world is always an uncertain place. China though presents more certainty about where it’s heading and how it wants to get there than any other major global economy. That investors are fearful of China presently, in the context of this surplus of certainty, seems perverse.

Preamble

The UK has just voted for ten years of political and economic confusion. That such a large economy in the EU has put itself in this position means certain uncertainty for its neighbors for at least as long.

No matter how many arrows Mr. Abe fires at the Japanese economy a demographic headwind and intractable xenophobia condemn it to an interminable creep.

In the U.S. a toxic political environment and the specter of a nativist leader together with an economy that functions only in the very unreal condition of free money makes even the short term outlook an impossible to solve equation.

In stark contrast China presents certainties (not all beneficial for investors it should be noted) that we can, with a very high degree of confidence, predict will persist for at least the next decade. In this note I want to discuss these but it will help if I address first the bigger issue of…

Where Does China Want to Go?

I was at a talk recently in Hong Kong by Professor Liu Mingkang, formerly Chairman of the China Banking Regulatory Commission. As an articulate insider he’s always worth listening to but one part of his talk struck me especially. China’s broad development goal he told us is to have cleared the middle-income-trap by 2030 and to then achieve per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) equivalent to half of the U.S. by 2050.

The goals are less audacious than they sound. First, clearing the middle-income-trap. Defining this is hard because its less about income and more about structural economic progress. Two countries frequently referenced as stuck here are South Africa and Brazil. It’s their inability to progress up a technology curve and re-balance their economies that’s at the heart of their problems not their per capita GDP per se.

In terms of income China is already at the middle income stage. According to IMF forecasts for 2015 it’s per capita GDP, in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) International Dollars (Intl.$), was Intl.$14, 107. The world average was Intl.$15,638 and Brazil and South Africa were at Intl.$15, 615 and Intl.$13, 165 respectively. Assuming, in money terms, the Professor is thinking perhaps about Intl.$20, 000 when he talks of surpassing this phase then by 2030 (assuming the world grows by 1.5% for the next 15-years?) the target becomes c. Intl.$25, 000 requiring only 1.5% per annum growth to achieve it. Not a big reach. [I’m leaving the argument about economic structure out here. That would require a whole separate note.]

Achieving per capita GDP half that of the United States by 2050? Let’s assume the U.S. can grow their 2015 number of Intl.$55, 805 by 1.5% per annum to 2050. That’d lift it by around 68% to c. Intl.$94, 000. So China would need to achieve Intl.$47, 000 at that time. From their 2015 Intl.$14, 107 starting point to Intl.$47, 000 is a lift of 233% or a rise of 3.5% per annum. A bigger reach; but not an impossible one.

How is it Going About Getting There?

Listening to Professor Liu I started to think about more specific changes China is likely to be undergoing, not in the next fifteen or thirty-five years. Of more importance to investors, the next five or ten.

Using the reference of successful development models observed in the region together with a commonsensical what’s-most-likely approach it’s possible to predict changes ahead in China with a degree of certainty not possible in more developed economies.

Investors have a preference for certain outcomes and for some concerned about short term prospects it might be useful to stand back and consider the broader canvas. Thinking through where some things, specifically, are heading may help steady nerves jangled by events of the last year.

Seven Certainties

There are seven trends I want to highlight and in order of certainty (subjective, of course) I’ll begin with..

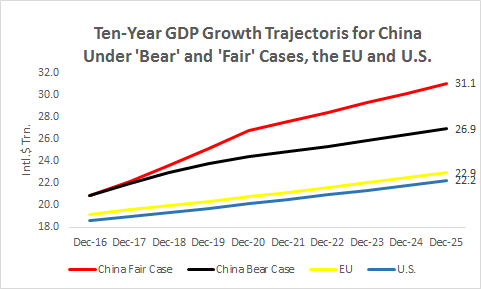

#1 Economic Growth. Everybody knows the glory days of China’s ultra-high growth are behind it; but what lies ahead? In the chart below I’ve made the following assumptions for growth for the next nine years (the starting points are all IMF forecasts for 2016).

China Bear Case: Fade growth from 6.5% in 2016 by 1% every year for the next four years and project 2% flat after that to Dec-2025 i.e. 5.5%, 4.5%, 3.5%, 2.5% and 2% thereafter.

China Fair Case: Take Mr. Xi Jinping and his planners at their word. Assume 6.5% growth to 2020 and 3% after that i.e. 6.5% per annum for 2017~20 and 3% per annum for 2021~2025.

EU: 2% flat per annum for 2017~2025. A fair assumption in light of recent events, no?

U.S. 2% flat per annum also for 2017~2025. Harsh perhaps in light of America’s proven ability to recover from adversity. Chances though of a toxic and adversarial political environment persisting are high.

It may surprise some to note China in 2016 is already the world’s largest economy (granted, in PPP terms); but see what happens in either the bear or fair case. It’s economy increases in size by either 29% or nearly 50% by 2026. The EU and U.S. grow by a little over 19% over the same period.

Today China’s economy is 9% larger than that of the EU and 12% larger than the U.S.; by 2026, in the ‘bear’ case scenario, China’s economy will be 18% larger than the EU and 21% larger than the U.S. In the ‘fair’ case scenario, it’ll be 36% bigger than the EU and 40% bigger than the U.S.

This is going to happen. Not maybe, perhaps or possibly, but with mathematical certainty. Global investors, presently underexposed to China, will have no choice but to adjust to this reality.

#2 Scale. If the economy is going to grow by something like 40% [From hereon I’m going to work with the mid-point of the bear and fair cases above] in the next 10-years many other things will need to grow with it.

Some things, like power consumption, will grow at a slower rate. Some things, like demand for cosmetic surgery, will likely grow at a faster pace. The important point though is that many businesses will not only continue to be viable but most are going to have to get bigger.

The steel industry will not shut down, more power stations will be required, more airports, rail track, subway systems, homes, autos and popsicles will be required in China in ten years’ time than today. Investors therefore should not lose sight of how ‘old’ economy businesses will continue to be important for a long time.

Presently there’s a notion that only new economy related businesses have a future. This has produced a dangerous concentration of interest in the stocks of the largest and most visible standard bearers of this sector; this will inevitably correct. At that time old economy operators may be a good home for funds in the context of the continuing viability of businesses linked to the scale imperative.

#3 Urbanization. So much has been written on this I don’t need to labor the point. The forecasts vary, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Redevelopment (MOHURD) some time ago predicted 300-million people moving from country to town between 2010 and 2025. China Vanke’s Chairman in the company’s 2015 Annual Report talked of 170-million moving off the land in the next ten years. All commentators seem to agree on a target of 70% for urbanization as a desirable and achievable near term goal (MOHURD talk of achieving this by 2030, the World Bank 2050).

Let’s run with Vanke’s number for souls heading for the cities. 170-million new urban residents in the next ten years. Assume 3-people to a home then there’s a demand for 60-million new homes or 6-million* per annum for the next ten years just to adjust for this movement; and that doesn’t scratch the surface of demand from existing urban residents either upgrading or forming new households. [*To put this number into context the U.S. completed an average of 1.44-million new homes per annum from 1959-2016.]

These new urbanites will need schools for their children, hospitals, cinema’s, parks, drinking water, sanitation. On top of this existing urban dwellers are demanding increasingly better facilities as the compact with their government continues to shift from a demand for improved material well-being to a desire for a better quality of life.

This again is not a maybe, a perhaps or a possibility. Bear this in mind when you hear, as you inevitably will, the next story about overbuilding in China’s cities. The reality, especially in the mega-cities, is that in many areas the development agenda may be dangerously behind the curve.

#4 Consumption. More pork, more noodles, more water, oh and more popsicles. More, more more of everything will be consumed in China ten years from now than today.

The rate of growth of many consumption trends may have slowed but the trajectory remains unequivocally up. This is especially important for the rest of the world. Whether you’re an investor in Chilean copper mines, U.S. soy bean growers or French handbag mongers, don’t confuse the recent shift in the pace of growth with the volume of demand. The former has decreased some, surely; but the latter will continue to rise.

An aside here on picking stocks in this area. For investors looking for businesses in the domestic market most likely to benefit from this trend, best of luck. Companies doing a good job today are conspicuous by the stratospheric valuations of their stocks.

The graveyard of former consumption darlings* is a crowded one and contains an important lesson for investors in today’s hotties. I often wonder how the same investors who understand that the certain aggregate rise in future airplane sales doesn’t necessarily translate into attractive airplane maker’s stocks forget this principle (over and over again!) in the China retail/consumption sector?

The bottom line here is this is surely a trend that will persist for the next ten years. If you plan to invest though maybe you’ll make some money, perhaps you’ll find some durable winners but there’s a strong possibility you’ll be overpaying to participate.

[*Just a few examples (with 5-year stock price performance/falls from peak, in alphabetical order): Brilliance China 1114 (-13%/-53%), Hengan 1044 (-11%/-36%), Parkson Retail 3368 (-94%/same), Tingyi 0322 (-70%/-72%), Want Want 0151 (-28%/-56%).]

#5 Development of the Finance Sector. A shibboleth of the Chinacynicus-tribe is this is where dragons truly be. My view? If you chose to believe the world is supported on elephants riding a turtle the burden of proof is on you. It’s not for me to upend your argument; it’s for you to convince me, preferably with facts, of the validity of yours.

That China’s finance system is a work in progress is not in contention; but is it a ticking bomb of undisclosed losses, unrecorded shadow dealings and Party goons lending to cronies in zombie companies? I’ve never seen hard evidence to support the notion that these are systemic issues. Here and there some of these practices are uncovered from time to time, sure. They’re also regularly exposed in other financial systems the world over.

Let’s think though about the next ten years. Putting aside the notion that a KA-BOOM! is just around the corner what can we say, with reinforced-concrete certainty, about the future for this sector? Three things; it’s going to get bigger, it’s going to endure and it’s going to get a lot more complex.

Bigger? If the economy is going to see a 40% lift the finance sector isn’t going to stagnate. Loan growth will need to expand to support the larger economy. Savings will continue to bolster the liability side of balance sheets and customers will demand an increasingly more diverse range of products to serve the needs of their changing lives. Could today’s incumbents be seriously dis-intermediated and/or disrupted though? Some think so. Looking at trends in developed markets though my best guess is the big stay big; but there’ll be sufficient room for a number of new players offering sufficiently differentiated products that both the big and the small, the old and the new will find space to successfully coexist.

Endurance? Here are two simple questions? Can you be completely sure, in ten years’ time, there’ll be a Barclays, a Deutsche Bank or even a JP Morgan still in existence? On the other hand, in ten years’ time, do you believe you’ll still be able to transact with the Bank of China, ICBC or The Agricultural Bank of China? Whatever your answer to these questions you’d probably at least agree the shorter odds are on the latter scenario? What’s regularly overlooked in discussions about this sector is how diminished risk is when a single operator, the state, controls both sides of the balance sheet. Problems in other systems, Japan, the U.S. and Europe have occurred when operators have lost control of one, or both sides of their balance sheets and their governments are powerless to quickly mend the problem. This is not a scenario that can, or will be allowed to, happen in China.

Complexity? D’uh! The progress of human achievement is one of ever increasing complexity. Autos, smartphones, disposable razors; the proof is all around. I wish they didn’t but financial systems seem to also follow this pattern. China’s financial system today would be familiar both to Jacob Fugger (the Rich) or Cosimo de’ Medici; because it’s practically medieval in terms of its simplicity. Not since Zhu Rongji (with, it should be noted, the support of his boss Deng Xiaoping) has China shown much appetite for bold finance sector reform. The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) helped reinforce conservative notions that innovation in financial markets is nearly always a bad thing (they have a point, junk bonds – Milken, Boesky and friends, derivatives – Baring’s collapse, securitization – the GFC); but things have to change. This may be where dragons really be; but it seems inevitable the system has to head in this direction.

#6 Military Capability. China now has one aircraft carrier in service and on December 31st last year it was reported that another is under construction. It’s since been reported that in fact two more carriers are under construction, both of an entirely indigenous design. As far back as 2011 a spokesman at the Academy of Military Sciences justified the need for three carriers as that would equal the number Japan[ [?] Who in fact don’t have any] and India each had. Reports of two more in the pipe then seem consistent.

China increased its defense budget by 9.5% per annum from 2005 to 2014 and in 2015 it increased by 11%. At 2.1% of GDP it’s some way behind the U.S. who spend approximately 3.5% of GDP; but it’s now the #2 military spender in the world.

They maintain a nuclear capability, have an ambitious military-sponsored space program and are home to some of the world’s most accomplished cyber warriors. Even if defense spending is capped as a percentage of GDP with that GDP expected to grow by 40% in the next decade it’s not hard to see where this is going?

China claims it’s not a belligerent. In living memory though unconditional engagement in the Korean war, a hot border dispute with India in 1962 and an offensive campaign against Vietnam in 1979 remind that China has not been afraid to mobilize forces when they feel their interests have been at risk.

Somewhere inside the ‘nine dash line’ seen above is probably the place where conflict is most likely to be provoked in the next decade. A child looking at this map would immediately spot the absurdity of the claim to territoriality and, to be fair, China is not entirely adamant about this. Nevertheless, behavior to date has not been good.

On July 12th the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague is set to rule on a Philippine initiated case on the validity of the nine dash line (among other things). China has already served notice that it’s not prepared to accept any decision by the court as the issue concerns sovereignty, over which it maintains the court has no jurisdiction. So far so adolescent.

No one can predict how China’s bigger military might will affect the region over the next decade but what we can say, with authority today, is China will displace the U.S. over the next decade as the dominant military power in the region; the neighbors are unlikely to feel warm and fuzzy about this.

#7 Increasing Global Heft. Given the trends discussed so far this is a given. As Japan grew in terms of economic significance in the ‘70’s and ‘80’s they showed little interest in having a bigger say in international institutions. A pacifist constitution was the fig-leaf of respectability for this reticence and the taking on of greater responsibilities in terms of support for either peace keeping initiatives or more proactive aid policies (to be fair, they were the world’s second largest aid providers in 1991; but this was mostly to multilateral aid agencies and countries where business interests were assumed to be responsible for the flow).

China is different.

Unable to get a get a front row seat at the World Bank they’ve created their own alternative the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. A so-called ‘international’ initiative it is of course China’s show. This will in part support the One Belt One Road project, an infrastructure plan promulgated by China but one that aims to create infrastructure from Xi’an (the belt) and Fuzhou (the maritime road) to Rotterdam and Venice respectively. I’m not sure how many nations where infrastructure has been mooted were consulted before the plan was rolled out? India has already voiced reservations.

The Confucius Institute program, begun with its first facility opened in 2004 in Korea, as at 2014 had established just short of 500 offices around the world. The plan is to have 1, 000 operating by 2020. The Goethe Institute by comparison has 159 institutes worldwide. The program has been criticized for various reasons but its primary purpose is clearly the extension of China’s soft power. Also, unlike the Gothe Institute or the British Council the Confucius Institute is directly sponsored by the Chinese government via the Ministry of Education.

China therefore is very interested in making its presence felt internationally; but its new to the game and, particularly in regard to the neighbors, has been clumsy on occasion. There’s no predicting how this process will develop but the rest of the world will have to learn how to deal with an increasingly assertive, muscular and vociferous China in the decade ahead.

The Last Word – Politics

I’ve discussed certainties above but I thought I’d end with thoughts on perhaps the biggest un-certainty China faces in the decade ahead; politics.

We can’t know what’s in the mind of President Xi Jinping but we can see what he’s doing; and that’s concentrating power. If he’s a Lee Kuan Yew this might be the beginning of something really interesting and good. If on the other hand he’s a Mao Zedong? Lord help us all!

China can’t be governed without the assent of its people. Today the Communist Party of China and President Xi appear to have that. As the economy continues to develop though, as the middle class enlarges and as aspirations shift from a desire for material prosperity to a more holistic concept of well-being it seems likely that a more plural and accountable form of government will be required.

A multiparty democracy is out of the question; but a more open and accessible government supported by a truly independent legal system doesn’t seem like too radical a development to hope for? Of urgent concern today, we can see no such move in this direction or even a discussion (at least within China) of its necessity.

In Conclusion

China is set to get a lot bigger both in absolute and relative global terms. This is likely to be beneficial for its citizenry and the world in general. The goals have been defined even if the specific road maps are still being worked on.

That global investors are as underweight and fearful as many appear to be presently, especially in the context of such clarity on so many major issues, is strange. Moreover, when prospects for many in home markets are so unclear, China’s surplus of certainty seems to present a compelling argument for greater involvement.