Nial Gooding

Friday, June 20th 2014

Summary conclusion

A component of the decision to reverse the multi-year policy of Renminbi strength, I believe, was growth in the last two years of foreign currency liabilities assumed by Chinese borrowers. It’s too early to say whether this stitch-in-time action has been successful but if it has then the Renminbi is probably stable at current levels. If it hasn’t and foreign currency loans and bond issuance pick up as the year progresses brace for further weakness.

Preamble

China controls its exchange rate and I think this is a self-evident truth despite the regular denials.

Why then did policy shift this year and why was a multi-year strategy of gradual appreciation suspended and then reversed? The received narrative is that China responded to a weaker domestic economy and isn’t unhappy about collateral damage that’s occurred among nasty (mostly, but by no means exclusively) foreign operators of various forms of carry-trade.

This explanation, though plausible and maybe 75% correct, lacks something. The domestic economy has been steadily weakening since 2011 at least and carry-trade operators were at work for many years before this one. What happened earlier this year that pushed Beijing off the fence and prompted it to take the action it did? If we knew that we’d have a clue to whether or not they think they’ve done enough and what to expect next?

The lessons of history

Those who fail to learn the lessons of history are doomed to repeat them and policy makers in China have a strong sense not only of their own past mistakes but also the mistakes of others. I was surprised a while back at a planner-heavy forum in Beijing to hear the response to a question about whether China could go the way of Japan if it didn’t pay close enough attention to credit fuelled asset price inflation. The speaker-from-the-ministry didn’t hesitate; ‘We’ve studied the Japanese economy in depth, the bubble and the fallout and are determined nothing like that will be allowed to happen in China’. He continued ‘…we have also studied a great many other economies and their financial crisis, most recently the failure of the Western model, and our policy is guided by constant vigilance that the same problems will not be allowed to emerge in China’. Good answer and I’ll come on to the particular piece of history that may have been on policy makers minds a little further on.

China’s policy-Whack-a-Mole

The changes that China is going through, it’s vast geography and the increasing complexity of its economy means that the calm façade of central planners in Beijing hides the reality of day to day policy formation which is a multi-dimensional game of policy-Whack-a-Mole. Just when you thought you’d got one thing under control another problem pops its head up, often as an unintended consequence of an earlier policy (a good recent example would be the 2008 economic stimulus and real-estate prices).

What exchange rate related mole then most recently popped its head out and now needs a whack?

Whoomp! There it is..

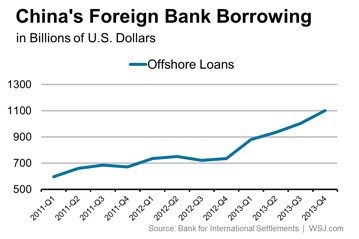

It’s not so much the number that’s the problem here; it’s the rate of change. From just over U$700bn at the end of 2012 the number had grown to over U$1trn by the beginning of 2014 or an increase of 43% in just one year.

The loans above at least could, if necessary because the majority are going to SOEs, be controlled with a dose of old fashioned ‘guidance’; but the overseas (mainly U$) bond issuance would be a much harder genie to re-bottle.

The rate of growth here again is impressive; 2012 U$29bn, 2013 U$58bn or +100%. I only have figures to April this year but it was over U$25bn which implies an annual total of U$75bn this year or growth of another 30%?

Of chickens, monkeys and moles

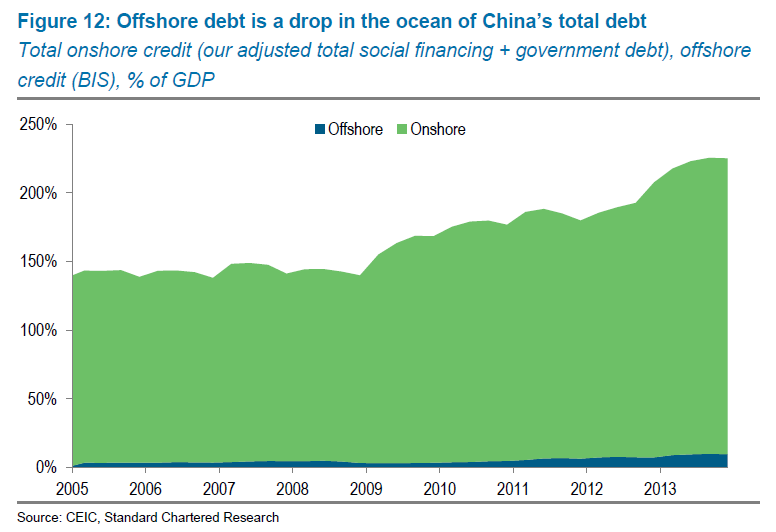

Despite the rapid growth of foreign currency denominated debt, as you can see from the chart above, it’s still a piffling component of China’s overall debt profile. It’s not a major problem today but I believe the lesson from history on planner’s minds is the one that brought Thailand, Korea, Steady Safe and others low in 1997 and was the root cause of the Asian Financial Crisis i.e. the danger associated with asset liability currency mismatches.

There’s an expression in Chinese about killing chickens to frighten monkeys but in this case I think the planners have let the chickens off with just a caution. The broader message is clear though; foreign currency debt can no longer be relied upon as a double happiness proposition that delivers both lower nominal rates and an ever shrinking liability.

In Conclusion

Referring back to the chart at the top of this note it seems the authorities are, in fact, all done for now with their downward Renminbi adjustment.

If part of the reason for the currency move was to give the export manufacturing complex a breather then time will have to pass to see if this is working. If another part of the reason for the move was to scatter the carry-traders that’s probably happened so there’s no need to revisit that lesson. Finally, if part of the reason for the move was to remind borrowers about the two way nature of the exchange rate then again, time will now have to pass to see if the message has been taken on board and the rate of foreign currency borrowing slows.

If however, as the year progresses, we see a fresh ramp up in foreign currency borrowing I’d start counting the days before the Renminbi was allowed to slip a little further. When all’s said and done though we mustn’t lose sight of the fact these moves are really quite small and what the authorities appear to be doing is hoping that a stitch-in-time will end up saving nine*. Keep a close eye on that bond calendar though.

[*Or, as they might say, 小洞不补大洞吃苦* (xiǎo dòng bù bǔ dà dòng chī kǔ)? A small hole not plugged will make you suffer (a bigger hole)]